The enchanting journey of calendars through the ages

Timekeeping and calendar systems are among the most fascinating but underrated sciences that we have tirelessly tried to perfect over the millennia. Here are two books to read on the topic.

Calendars and timekeeping have always mesmerised me. At four, I would tell you the day any date fell at the drop of a hat. Time zones fascinated me so much for days that a reclusive boy like me went to a well-travelled relative just to ask him whether wristwatches adjusted themselves on flights to match their new location. The day my parents got me a “digital diary”, I stayed up till midnight just to catch the date changing in real time. (I considered doing the same on New Year’s Eve too, but didn’t.*).

It was only in recent years that I began to realise that this quirk wasn’t as trivial or childish as I thought. As it turns out, the history of the world itself intersects surprisingly often with the history of the calendar and timekeeping. Think about it: when there was nothing, there was time. It’s always moving, only in one direction, leaving you with no option but to measure it, somehow. Early humans didn’t have any option either: and they scrambled hard to figure it all out.

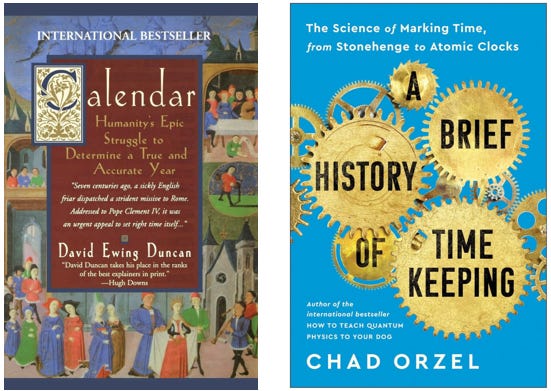

I just finished reading two breathtaking books: Chad Orzel’s A Brief History of Timekeeping (BenBella Books, 2022) and David Ewing Duncan’s Calendar (Avon Books, 1998), and I’m truly spellbound at how the quest for accurate timekeeping has shaped humanity at all its stages—even when our prehistoric ancestors were largely clueless about the world. In this post, I share what I’m thinking right now as I chew on these books.

Even when maths was scarce and the number system was in dinosaur age, there were the sun and the moon, mysteriously rising out of nowhere and turning off every day, acting as natural clocks, demanding to be tracked, somehow. And track we did—in ways small and big. It gave birth to a remarkable timeline of events, driven in turns by agriculture (think of the havoc farmers would be in if the calendar was linked to the moon and not the seasons), religion (think of the tensions it would create if two priests began arguing about when a festival should be held), and medieval imperialism (think of why the British Empire would announce a massive prize for anyone who could figure out how to measure longitudes—and hence time—at the sea, a real pain for scientists at that time).

The process ended up shaping everything from mathematics, physics and engineering to astronomy, geopolitics, and our GPS and satellite systems today. Innovations in each pushed all others ahead: humanity’s puzzles, across disciplines, almost always got their answers when we ‘timed’ it right.

War—and love**—led to the basis for the calendar we use today. A major tweak to how we count days once led to a riot^. How to decide the date of Easter (and the imperative to avoid a method that mimicked the rival Jewish calendar) was the subject of hot debate and mathematical innovation for centuries. It’s truly revelatory to think of world history from the perspective of the calendar.

While I strongly recommend you read the books, here’s my list of three characters who impressed me the most (among many) along the journey:

Su Song: A Chinese polymath who designed the world’s first hydro-mechanical astronomical clock tower in the 11th century. Till then, something or the other was not quite working out as people everywhere tried to measure time. Su Song solved several issues with a clock that likely weighed in tonnes.Ruth Belville (aka Greenwich Time Lady): A British woman who visited the Royal Observatory in Greenwich to reset her watch every week and then went door-to-door to meet (and chat with) all her subscribers so that they could sync their devices with hers. (Yes, clocks would need to be synced that often even in the 20th century—and it could be a bona fide business idea!)

Roger Bacon: The 13th-century British polymath who no one listened to when he insisted that the Julian calendar had an error, because of which it no longer aligned with the seasons. A pope who finally showed interest ended up dying before Bacon’s paperwork and calculations reached him in Rome. The remedy that Bacon had sought only came by in 1582. (In fact, the dating of Easter ultimately played a role in the correction of an imperfect calendar that had dictated the world for over 1,600 years. Had it not been for religion, would the leaders of those times have found it a matter critical enough that their calendar was sliding away against the seasons?)These are just a few names; of course scientists and mathematicians during the middle ages played integral roles in solving the biggest questions about our earth’s motions. Some of them fought with each other for credit and acceptance when they lived, but the truth that matters 400 years later is simple: they all built upon years of human thinking and philosophy, benefited greatly from each other at a busy time for scientific discovery, and together, set the path for future innovations that would shape the world we inhabit.

*I didn’t, because by then, I had learnt that I could change the time in the device myself whenever I wanted for any experiment.

**The reference is to Julius Caesar, his entry into Egypt, and his subsequent and tireless infatuation with Cleopatra.

^The reference is to the shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar in the UK in 1752, due to which 11 days just vanished from the calendar. (If it happened today, how much rent would you pay your landlord for the affected month?)

All information shared here is my interpretation of my reading of the two books, and my own research. I learned about Su Song and Ruth Belville in Orzel’s book, and Roger Bacon found mention in both books.